Takasaki - city of the daruma doll

A transport and business hub located just under an hour from Tokyo by shinkansen, the city of Takasaki has remained largely off-radar to the majority of foreign visitors, except perhaps as a stop on the way to Gunma's better known hot spring destinations. Despite its lesser-known status outside of Japan however, the city and its surroundings have played an important part in Japan's history, and - as I discovered on a recent two-day trip - still have a great deal to offer today.

As with my previous trip to Shima Onsen, what could have been a long and difficult planning process was made much easier by Gunma's official tourism page, offering a detailed list of suggested spots to visit, suggested itineraries and even a handy trip planning tool.

Day 1

My first thought as I stepped off of the shinkansen and into Takasaki Station was that it could have been any medium-sized commuter town within a certain radius of Tokyo. It wasn't until a few minutes later, as I sped out of the city center on the JR Shinetsu Line, that the landscape opened up to reveal a broad plain and the silhouetted outline of distant mountains.

Getting off at Gunma-Yawata Station, I made my way across the Usui River, pausing to take in the view of Mount Asama to the North West. A few hundred meters further along, I arrived at Shorinzan Darumaji Temple, my first stop of the day.

Belonging to the Obaku school of Zen Buddhism, Shorinzan is best known for its association with daruma dolls - a popular handicraft and good luck charm found throughout Japan. Usually made from papier mache using a strong, fibrous traditional paper called washi, the figurines somewhat resemble Russian babushka dolls - a rounded figure tightly wrapped in a priestly robe, with a bearded face peeping out from under the hood.

The character represented is the Bodhidharma - a legendary monk credited with bringing Buddhism to China, said to have sat in ceaseless meditation for a period of nine years. Even depicted as a doll, his face has a fierce quality, celebrated as a symbol of single-minded focus on a personal goal.

The origins of the daruma can be traced to the end of the 17th century, when Shorinzan's founder - a priest known as Shinetsu - began to give out simple paintings of the same figure to local farmers to protect them from misfortune in the year to come. Almost a century later, the temple's ninth head priest Togaku carved the first daruma from a piece of driftwood, before teaching the technique to the farmers as a craft to see them through times of famine. Today, over 80% of the dolls are still made by craftsmen in Takasaki.

From the temple's elaborate main gate, I climbed a long flight of stone steps to the upper precinct, lined with maple and ginkgo trees. Under the eaves of the main building, called Reifudo, hundreds of daruma dolls big and small were piled high along its veranda, creating a unique and atmospheric appearance.

Set just below the main precinct to one side is the temple's Kannon hall, an elegant building with a beautiful old thatched roof.

After taking in the main precinct, I spent a few peaceful minutes wandering through the temple's strolling garden, a simple but very pleasant space dotted with trees and bushes. A little off to the northeast, I came across an attractive little pavilion. Known as Seishintei, the building was once home to the German architect and writer Bruno Taut, whose studies helped to introduce Japanese aesthetics to the west. Inscribed in German on a simple stone tablet close by are his words I love the Japanese culture

.

From Shorinzan Darumaji Temple, I retraced my steps back across the river for the next stop on my itinerary. Belonging to the fourth generation master daruma craftsman Nakada Sumikazu, Daimonya Co., Ltd. is the largest and most celebrated workshop of its kind in Gunma Prefecture. Here, I would be learning more about the significance of the daruma, and get the chance to decorate my very own piece.

Taking a seat with a small group of other visitors, I listened as one of Daimonya's craftspeople further explained the traditions associated with the curiously shaped figurines. Originally sold at New Year's Festivals, they are intended to symbolize a particular wish or goal. Upon receiving the daruma, its new owner should first fill in its left pupil, representing the opening of one's mind, then display it within their home. When the goal is achieved, the right pupil can also be filled in, and the daruma eventually presented to a Buddhist priest to be burned as an offering.

Our craftsperson then showed us how to paint on the eyebrows and mustache with a series of quick, seemingly effortless brushstrokes - a characteristic of the Takasaki Daruma - explaining that the shapes are based on those of a crane and tortoise. After a few examples, including an easy

and hard

variation for each, it was time to give it a try.

Somewhat embarrassed, I handed my piece back to the craftsperson, who wiped a few beads of ink from the doll's robe and signed my name in graceful katakana script, the brush darting with practiced ease. As the group said our goodbyes, she observed something I would find myself thinking about later - a sense of calm concentration that had come over all of us while attempting this simple (or not so simple) task, as if bound up with the meaning of the thing itself.

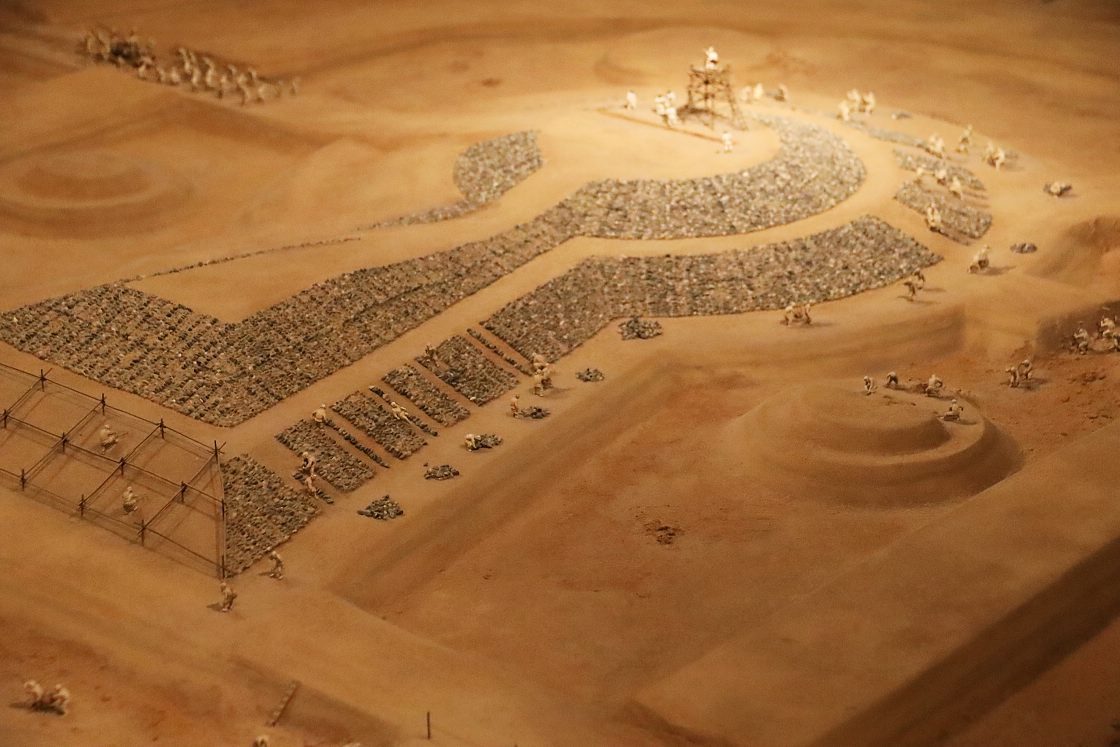

With my very own daruma safely boxed up, I took the JR Shinetsu Line back to Takasaki Station, then changed to a local bus for a 45-minute journey to the Hodota Kofun-gun, a cluster of three ancient burial mounds at the foot of Mount Haruna. Dating from the late fifth to early sixth centuries AD, these vast keyhole-shaped structures belonged to tribal chieftains who ruled the area to the southeast of Mount Haruna.

Appearing in various sizes and shapes in sites throughout Japan, kofun tombs give their name to a whole period of Japanese history from around 300 to 538 AD, until the arrival of Buddhism led to sweeping cultural changes. As belief in an afterlife gave way to a cycle of death and rebirth, vast monumental graves soon lost their significance and became a thing of the past.

Home to the greatest concentration and largest examples of the ancient tombs in eastern Japan, the area today known as Gunma was clearly an important power center, likely due to its role as a transportation hub, and its grassy plains being the perfect terrain to rear and train horses.

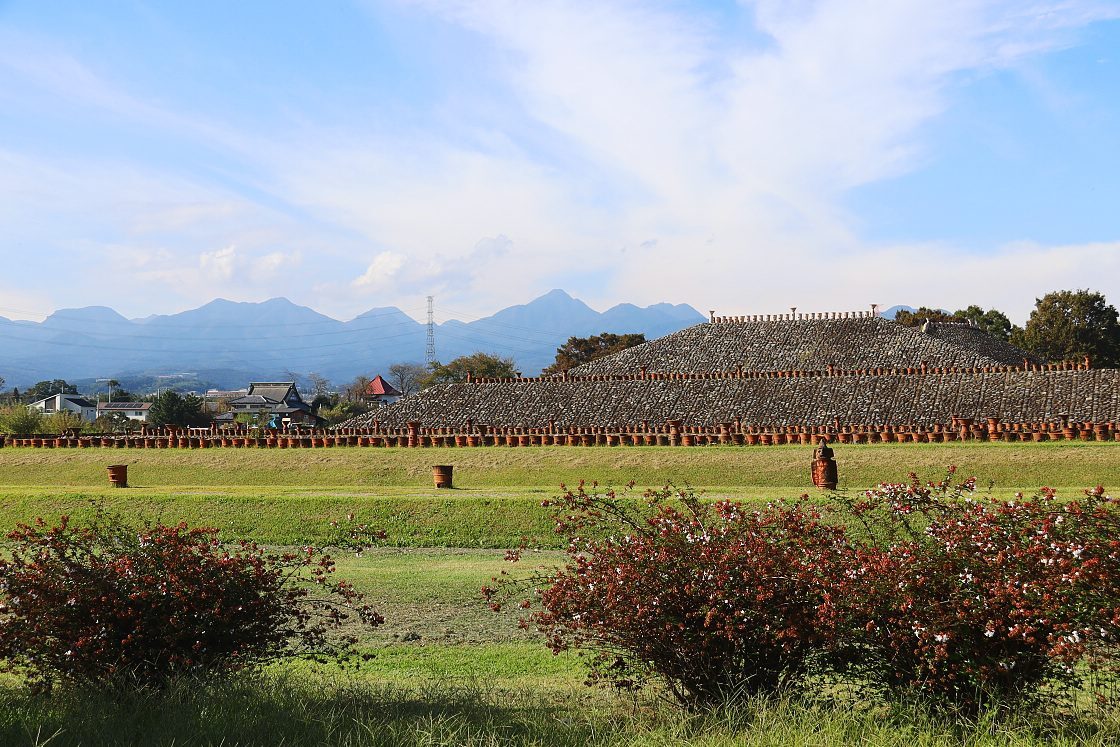

Of the three tombs here, one is particularly unique. While almost all such sites throughout Japan are overgrown with grass or even groves of trees, the Hachimanzuka Kofun has been painstakingly restored to something close to its original appearance, its slopes lined with smooth stones and rows of haniwa - clay figurines of humans and animals, each serving a specific ritual purpose and made in the highly distinctive style of the period.

Located just a few steps away in a field of colorful cosmos flowers, the Futagoyama Kofun is of similarly impressive dimensions, but a coating of grass has been allowed to form giving it a serene and natural feel. Climbing to the top, I was able to enjoy a beautiful view across the field and surrounding town to the mountains in the distance.

Between the two tombs in the same pleasantly grassy space is another highlight of my visit, the excellent Kamitsukenosato Museum of Archaeology, in whose permanent exhibition I found a range of fascinating items excavated from the mounds as well as a series of maps, models and diagrams shedding light on the civilization that built them.

Of all the items on display, the ones that impressed me most were the haniwa figures themselves. The more I looked at these apparently simple forms, the more graceful and serene they seemed. They also revealed an incredible level of detail, from the individual parts of a warrior's armor or horse's bridle, to the elaborate folds of an ornate hairstyle.

After another bus ride back into the city center I was definitely ready to head out for my evening meal, and while the area around Takasaki Station is packed with restaurants of all kinds, I was especially keen to try a surprising local speciality - Italian style pasta! In fact, with Gunma being one of Japan's leading producers of wheat, pasta has become a unique source of pride and rivalry among Takasaki's restaurants, giving rise to the King of Pasta Competition held in the city every year.

A two-time winner and two-time runner-up of the coveted award, Caro offers a range of sophisticated pasta dishes in a relaxed, casual setting just ten minutes from the station.

I started with a sea bream carpaccio, topped with leafy salad and a light, citrusy dressing. For my main course, I ordered pasta with locally reared ham, served in a cream source with a dash of wasabi - the same dish that won the King of Pasta top prize in 2020.

With a busy first day of sightseeing drawing to a close, I checked in at the Hotel Metropolitan Takasaki, a pleasant, unpretentious business hotel conveniently located within the Takasaki Station Building.

Day 2

Making an early start the following morning, I took the private Joshin Railway to Takasaki's smaller neighboring city Tomioka, home to one of the most important sites in Japan's modern industrial history.

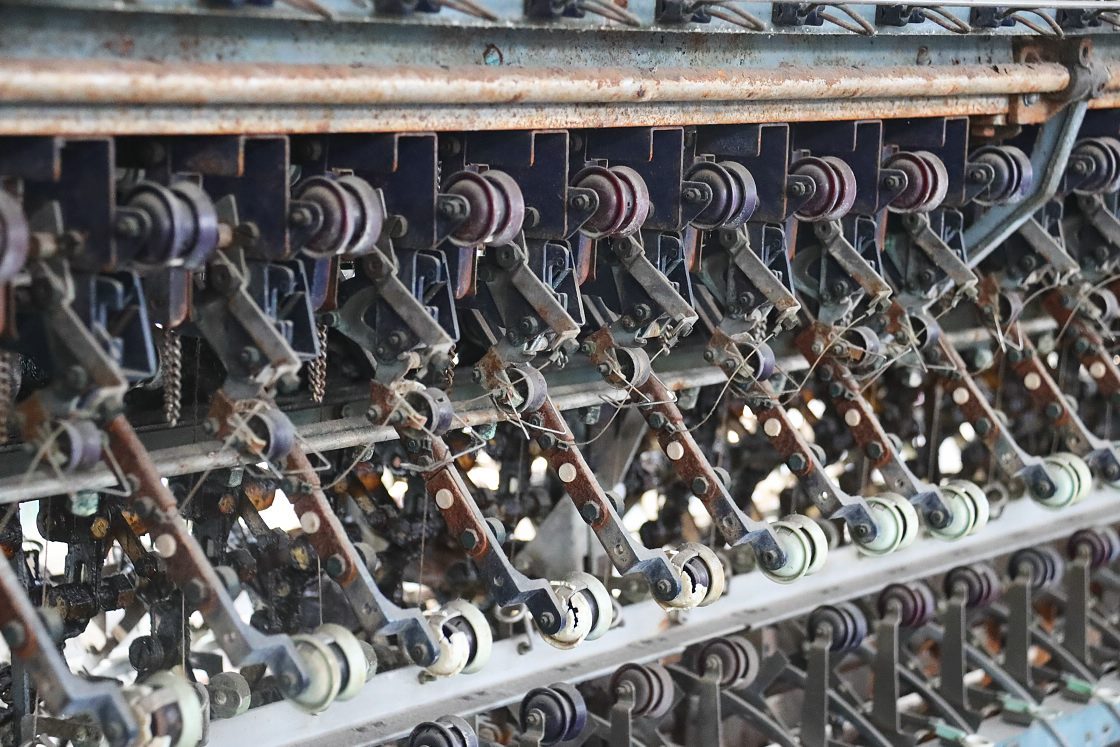

Established by the Meiji Period government in 1872 with assistance from French engineers, the Tomioka Silk Mill was the first factory of its kind in Japan and helped to revolutionize the nation's vital silk industry.

Spread out over a large compound, the mill comprises a series of brick and timber buildings, including offices, dormitories, warehouses and the silk reeling mill itself, where visitors can see the machinery used when the factory closed in 1987.

Another highlight for me was the West Cocoon Warehouse, where a series of exhibits can be found providing a glimpse of what life for the mill's largely female workforce was like, as well as the methods and materials used in the building's construction. A particularly impressive detail is the overlay of glass and steel, a recent addition to protect the structure from earthquakes while revealing the skeleton beneath.

After a very enjoyable few hours exploring the mill, it was time to make my way to a traditional local restaurant where I had arranged for a very unique dining experience built around another of Gunma's culinary specialities.

Located in a stately former residence, Tokiwaso specializes in elaborate kaiseki cuisine with an unusual twist - almost all of its beautifully presented dishes are made with konnyaku, a thick, starchy vegetable jelly made from the corm of the konjac plant. A popular and extremely versatile ingredient, 90% of the konnyaku produced throughout Japan in grown right here in Gunma Prefecture.

Taking a seat in one of the elegant former guestrooms, I had a few minutes to enjoy the view of a pristine little garden before my first course arrived - bites of konnyaku on little sticks, konnyaku noodles in a sticky soup made of shaved yam and delicate slices of konnyaku sashimi served with a sweet, tangy miso sauce.

These were soon followed by more light and perfectly formed little dishes, last of all being my personal favourite - chunks of konnyaku wrapped in tangy shiso leaves and deep fried in tempura batter.

Finishing my meal with a refreshing bite of persimmon ice cream and a last, lingering look at the beautiful garden, it was time to move on. My time in Takasaki and Tomioka was already drawing to a close, but there was still time for one last stop at the venerable local temple, Ryukoji.

Belonging to the Jodo school of Buddhism, Ryukoji was originally built around 1460 in the nearby village of Miyazaki, at a time when what is now Gunma Prefecture was only sparsely populated. By the early 17th century, the town of Tomioka was beginning to grow and the temple was relocated here, along with its cast iron temple bell and the large ginkgo tree that still stands in its grounds.

As I made my way inside, I was drawn to the graceful shape of the temple's main gate. Taking a closer look, I noticed that its pillars were covered in a patchwork of hand-carved geometric patterns.

Today, the site is best known for an important, if somber connection to the Tomioka Silk Mill. Over the years, thousands of people found employment at the mill, many of them young women separated for the first time from families in other cities. Despite on-site medical care and working conditions that were progressive for their time, as many as 54 female machine operators passed away during their time at the mill and are interred in the temple's graveyard.

Another interesting feature is a curious stone tablet known only as the Itabi, dedicated to an ancestor of the temple's founder long since lost to time. Above a simple inscription dating it to the year 1364 is a five-syllable mantra, each character interlaced to form a design resembling a five tiered Buddhist pagoda.

After enjoying a few last moments in the peaceful space, I began to thread my way back through Tomioka towards the station and my journey home. Despite setting out with little idea of what to expect, my two days here had turned out to be a genuine delight, with much to recommend.

Access

From Tokyo, take the Joetsu Shinkansen (around one hour, about 5000 yen). Alternatively, take the Takasaki Line or Shonan-Shinjuku Line (around two hours, 1980 yen). Either method is covered by the Japan Rail Pass and Tokyo Wide Pass.

For Tomioka, take the Joshin Railway from Takasaki to Joshu-Tomioka Station (around 40 minutes, 810 yen). Joshin Railway is covered by the Tokyo Wide Pass, but not by the Japan Rail Pass.