Hemmed in between a ruggedly beautiful stretch of the Japan Sea coastline and a magnificent range of mountains to the south lies an area of the Chugoku region whose spectacular scenery, rural charm and fascinating local traditions make it the ideal destination for visitors searching for an authentic, under-the-radar experience.

Known as the Land of the Kirin, the area encompasses Tottori City and the towns of Iwami, Wakasa, Chizu and Yazu in the eastern part of Tottori Prefecture, as well as Kami and Shin-Onsen in the northern part of Hyogo Prefecture.

On a three-day trip last autumn - my first time in this part of the country - I had the chance to explore some of this unique area's best-known sightseeing spots and find out first hand just how much it has to offer.

Day 1

My journey began at Amarube in Kami Town, about 40 minutes from Kinosaki Onsen Station on the JR Sanin Line, once well-known for a giant and brightly painted trestle bridge passing between the mountains on each side. Completed in 1912, the Amarube Viaduct was the largest of its kind in all of Japan, and the cornerstone of an immense undertaking to connect the towns of Kami and Shin Onsen over challenging, mountainous terrain.

In 2008 the bridge was replaced with a modern concrete structure, but several sections of the original bridge still stand at the western side, and a glass elevator called the Crystal Tower has been added allowing quick access between the station and valley below.

Just a few steps from the crystal tower, I found the entrance to a pleasant walking route leading up the wooded hillside to the east of the valley. As I approached the top, I was able to catch a glimpse through thick undergrowth of the Amarube Viaduct and a distant hillside village called Misaki, said to be one of several on the Sanin coast founded centuries ago by a handful of Heike survivors after their defeated at the battle of Dan-no-Ura.

The path, just one section of a larger trail spanning the length of the Sanin Kaigan Geopark, continued eastward along the rocky, forest covered coastline, leading to a picturesque little fishing village called Yoroi. The name, meaning armor, comes from a nearby rock formation said to resemble a samurai's mailed sleeve.

From Yoroi, I took the Sanin Main Line three steps west to Hamasaka, an old part of Shin Onsen known for its historic merchant houses. After collecting a rental bike from the tourist office opposite the station, it was just a three-minute ride west to Utsuno Jinja, a shrine dedicated to Susanoo no Mikoto, brother of the sun goddess Amaterasu.

One of the shrine's interesting features is a statue showing the Kirinjishi-mai, a sacred dance unique to the region and performed at shrines during spring and autumn festivals. Introduced by the former feudal lord of Tottori in 1652, the dance has remained an important part of local culture, with many local shrines boasting their own unique costume and mask.

Originating in Chinese mythology, the kirin itself is a kindly mythical creature combining the features of a lion, deer, dragon and ox, said to bring good fortune and ward off danger.

At the top of a flight of stone steps and surrounded by tall trees, the shrine's main building is an elegant wooden structure with hanging bronze lanterns and some elaborate carvings.

Retracing my steps to the area around Hamasaka Station, I made a stop at Misakiya Cuisine, an unpretentious and very inviting local seafood restaurant where I enjoyed a hearty bowl of kaisendon - fresh sashimi, boiled crab and salmon eggs layered over a bed of rice and vegetables.

Back on my rental bike, I took a short ride north of the station to the Imeitei Pioneer Hall, a stately wooden townhouse that was once a sake brewery and residence belonging to the local Mori family of merchants, now attractively renovated and serving as a local museum.

Like many machiya-style houses, the Imeitei is larger than it appears from the front, with a tamped-earth floored entrance area leading into a series of connecting tatami rooms, with an enclosed garden courtyard and separate storehouse. As well as some displays about the Mori family and the history of the town, the house contains a trove of antique furniture, tools, prints and calligraphy.

Located 15 minutes walk from Imeitei along the banks of the Kishida River is the Hamasaka Sun Beach, a picturesque stretch of sand especially popular in summer. Sadly, it was already a little late in the year for summer sun, and powerful winds were gusting in from an approaching typhoon.

After taking a few minutes to enjoy the rough sea and bracing wind, I made my way back to Hamasaka Station and returned my rental bike before jumping on a train for the 50 minute journey back to Tottori City. From there, I took a bus to my next stop of the day at the Watanabe Museum of Art.

Built to showcase an astonishing collection of antiques amassed by local doctor Watanabe Hajime over a 60 year period, the museum houses around 30,000 items from across Asia. While a wide range of different items can be found on display, the greater part of the museum is devoted to samurai arms and armor. As a devoted fan of Japanese history, I was delighted to find such a varied and fascinating collection, and every turn revealed a new surprise.

While the lack of detailed English information may be a limiting factor for some visitors, many of the items were displayed with a QR code leading to a short explanation online.

Finally tearing myself away from the museum's wonders, I took a ten-minute bus ride to my final stop of the day at the Tottori Castle Ruins. Once the seat of Tottori's ruling Ikeda family and an important regional power center, the castle was demolished during the modernization of the Meiji Era, leaving only its defensive walls partially intact. Since 1959 however, the walls have been restored thanks to a determined local effort, and today offer sweeping views of the city and surrounding hills.

Standing at the foot of the castle ruins is a stately European-style house called Jinpukaku, built by Tottori's former feudal lord as accommodaion for the visiting Crown Prince Yoshihito (the later Taisho Emperor). From its artful wood construction and modern decor to its use of electric lights, the house became symbolic of the region's modernization and was later taken over by the city to serve as a public meeting hall and museum.

Day 2

The second day of my time in the land of the Kirin began with an early start and an approximately 30 minute ride by Limited Express from Tottori Station to Chizu, a logging town surrounded by picturesque forest. About thirty minutes on foot from the station, my first stop of the day was at the Sugi Shrine, a unique Shinto shrine erected in 1955 with local funding to honor the spirit of the surrounding cedar forest. Unlike the vast majority of shrines where resident deities are given their own building to live in, here the object of worship is a large triangular structure representing the shape of a cedar tree.

A short walk uphill and just within sight of the shrine is a beautifully clear waterfall also said since ancient times to be home to a local spirit, and a tiny shrine with a distinctive triangular roof stands to one side.

From the shrine, I took a twenty-minute taxi journey deeper into the valley along the winding Kitamata River. Spread across six thatched-roof buildings in idyllic forest surroundings, Mitaki-en is a restaurant specializing in sansai, or traditional mountain cuisine, made with fresh local produce. Many of the ingredients are grown on-site giving it the feel of a small farm, with roaming chickens, little vegetable patches and standing logs used to cultivate shiitake mushrooms.

Visitors are also free to explore the surrounding woods, with strolling paths leading past moss-covered rocks and clear streams.

From Mitaki En, I made my way back down through the valley to the nearby Ashizu Shrine, just in time to catch a performance of the Kirin Jishi Mai dance as part of the annual autumn festival.

With slow and stately movements, two dancers wearing the familiar red, green and black costume of the kirin adopted a series of poses, accompanied by the rhythmic sound of drums and flute, and a mysterious figure called the shojo with a red mask, hair and staff. Derived from Chinese mythology like the Kirin itself, the shojo is an imaginary animal from noh theater with a special fondness for sake, who always appears alongside the beast to act as its guide and playmate.

Chatting to some of the spectators, I learnt that the performance would usually be just one part of a lively event called the Hanakago Matsuri or flower basket festival, in which a man from the town would be selected to carry a basket full of brightly colored sticks to dedicate to the shrine. Later, the sticks are given out to local people, who bend them into hoops and throw them onto the roofs of their houses for good luck in the coming year. Sadly, the event was cancelled this year due to the coming typhoon.

From Ashizu Shrine, I made my way back to my next stop at the Ishitani Residence, a grand stately home belonging to a wealthy family of timber merchants, with a picturesque background of cedar forest. Completed in the 1920s, the house incorporates a residential wing and storehouses of the family's original Edo Period building, with the whole complex set within a samurai-style walled compound.

Passing through the gate and into a small courtyard, visitors are faced with a formal entrance to the side leading to a section of the house with reception rooms and a teahouse, and the main building, built around a vast room with an open ceiling and earthen floor in the traditional style of a large farmhouse.

As timber merchants, the Ishitani family made every effort to showcase their special expertise throughout the house's construction, from giant beams of red pine in the entrance hall to verandas built without pillars allowing unobstructed views of an elegant landscape garden, designated as a National Scenic Spot. Intricate handcarved details can be found throughout, as well as unusual woods like Yakushima Cypress and Japanese Elm.

From the Ishitani Residence, I made my way back to Chizu Station and took a train to Wakasa, taking a little over an hour. My first stop here was a section of the main road, often called Kariya Street after the wide eaves on the traditional townhouses here. The town was once a popular rest stop for pilgrims, and many of the old houses still have small openings in the slatted wooden fronts, so that residents could reach out and offer alms to those passing by.

While exploring the street, I made a stop at Tonkatsu Arata, a family-run restaurant located in a 130-year old folk house with a delicious menu of local favorites, where I enjoyed a very tasty dish of tonkatsu before continuing on my journey.

On the narrow backstreet behind the main road, visitors can walk between neat rows of traditional buildings and temples.

A 15 minute bus ride from Wakasa Station to the south of the town stands the Fudo-in Iwaya-do, a fascinating Buddhist temple built on an elevated wooden stage within a hillside cave. Originally built around 1200 years ago by expert carpenters from the Hida region, the temple grew over several centuries into a thriving monastic community. The surrounding buildings were destroyed in the 16th century by the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi on his way to lay seige to Tottori Castle, leaving only the Fudo-in Iwaya-do itself standing.

The current building is around 600 years old, and largely unchanged since its peak in the 14th century. As well as its unusual architecture, the temple is known for a prized statue of the deity Fudo Myo-o said to be carved by Kobo Daishi, a leading figure in Japan's religious history.

From the temple, I took a bus back into the town and made my way to Wakasa Station, an attractive building recently remodeled in the style of the first half of the 20th century. From its rustic construction and period-style ticket office to finely carved wooden fittings, the station exudes a welcoming, nostalgic atmosphere that perfectly matches the feel of the town.

Jumping on one of the elegantly refitted trains, I took a very scenic thirty-minute ride from Wakasa to Koge Station along the Hatto River, passing villages, fields and wooded hills.

From Koge Station in Yazu Town, I took a Yazu Town Bus twenty minutes south into the Oe Valley to the Oenosato Nature Farm, one of the region's best known producers of cakes. The farm's signature ingredient is its own free range eggs, called tenbi-ran, said to add a uniquely fluffy texture to the pancakes offered here. Today, the site includes a bakery, cafe and restaurant in a modern glass building with sweeping views of the surrounding valley.

About twenty minutes on foot south of Oenosato Nature Farm is OOE VALLEY STAY, a unique hotel located in a reclaimed former elementary school. While the interior of the main building has been stylishly renovated in a sleek, minimalist fashion, the exterior, sports field and even the separate gym building have been left intact, giving it an unusual and fun atmosphere.

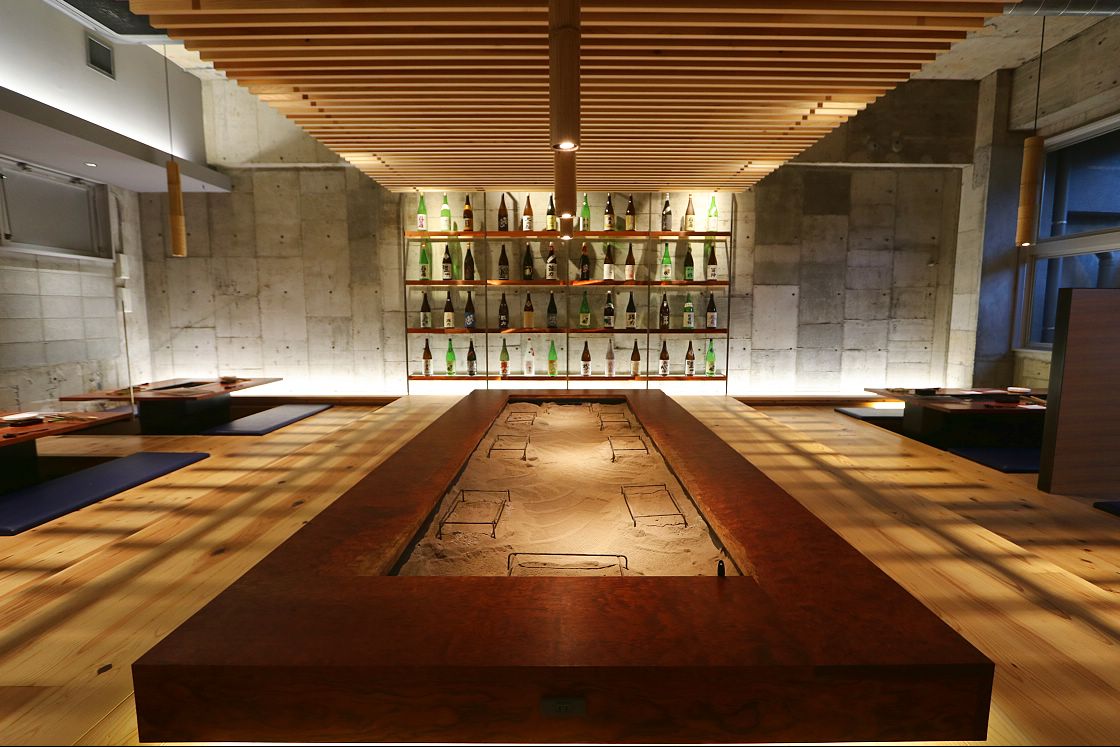

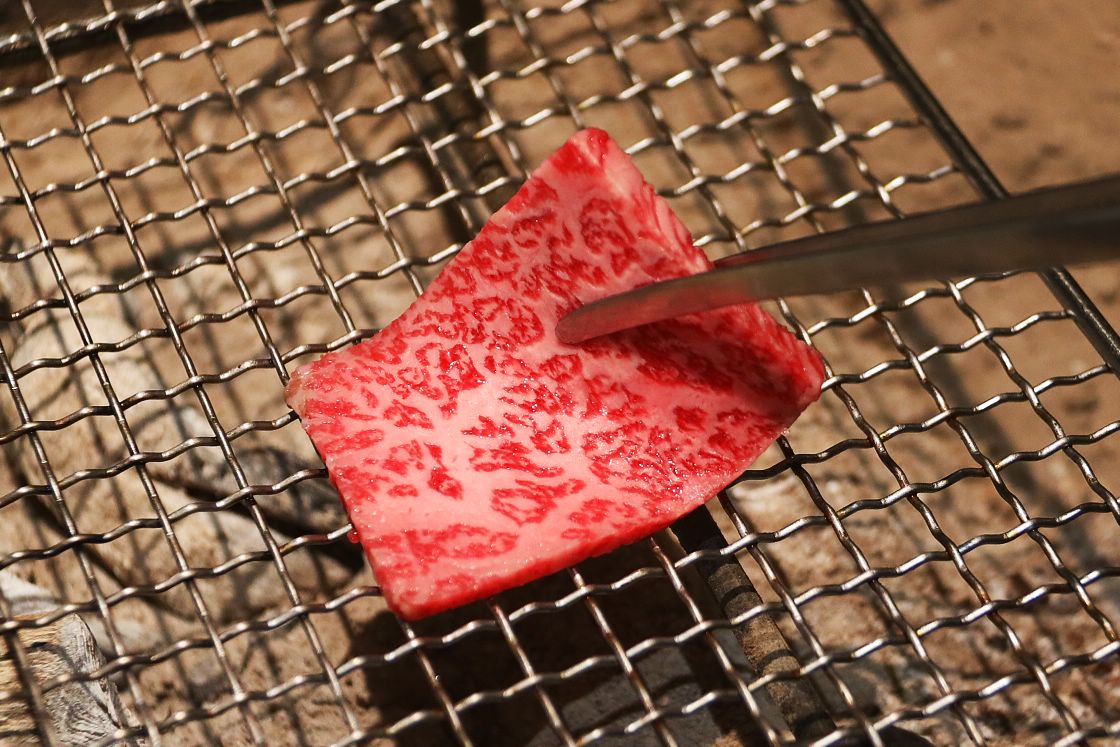

After checking in, I was treated to a beautifully presented kaiseki-style course banquet in the hotel's restaurant, Irori.

Day 3

After making my way back to Tottori City by bus and train, I began the last day of my trip at the Tottori Folk Crafts Museum, boasting a collection of 5,000 work brought together by Shouya Yoshida - a local doctor whose lifelong passion and advocacy helped to establish an influential local folk craft movement. While English explanations are somewhat limited, visitors to the museum can enjoy a beautiful selection of handmade pieces from ceramics and furniture to woven textiles.

A twenty minute bus ride from the city center by the famous Tottori Sand Dunes, the Sand Museum is the world's first attraction dedicated to large-scale works of art made entirely of sand. Handmade by an international team of expert craftsmen, the sand sculptures include complex tableaus up to several meters in height, with each year bringing a new theme.

This year's exhibition marks the 100th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Japan and Czechoslovakia, now separated into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, with spectacular townscapes, legendary figures and episodes from both nations' histories.

By now starting to feel a bit peckish, I made a stop at the Sakyu Kaikan, a tourist center offering meals, snacks and souvenirs. Having gained something of a taste for the local kaisendon, I ordered the largest portion possible - a feast of shredded crab, fresh shrimp, salmon eggs and creamy raw sea urchin.

After gorging myself on delicious local seafood, I jumped in a taxi to the town of Iwami, 30 minutes ride east along the coast. Here, I embarked on the Uradome Coast Island Sightseeing Cruise, taking in some dramatic views of jagged, weatherbeaten rock formations as the boat bounced along through a bracing wind and choppy waters.

With my visit drawing to an end I made my way to the Tottori Sand Dunes, a strikingly beautiful feature and by far the largest of its kind in all of Japan. Spanning 16 kilometers of coast, the dunes are the product of an unusual and highly intricate geological process, formed from sediment drawn from the Chugoku Mountains by the Sendai River, then dredged by tide and deposited on land by harsh winds gusting over the Sea of Japan. The same winds are constantly reshaping the dunes, leaving a distinctive rippling surface pattern.

As well as being a perfect spot to stroll and enjoy sweeping ocean views, the dunes' height and gently curving slopes make it perfectly suited to sandboarding. Joining a small group of other first-timers, I made my way to one of the smaller dunes by the ocean's edge, and after a quick demonstration, it was time to give it a try. Having never skied or snowboarded I was expecting to struggle with my balance, but after a couple of bumpy first tries I was able to make it to the bottom in one smooth descent. It was great fun, and I was soon rushing back to the top to try again and again.

With the sun beginning to set, I took a short stroll along the crest of the dune, enjoying the sand underfoot and the view out to sea before slowly making my way back towards the town.

With the light quickly, there was time for just one final stop at the Tanegaike Benten-gu Shrine, located in a stretch of woodland along the Tanegaike Pond, a short walk east of the Sand Dunes. Dedicated to Benzaiten, a fertility goddess said to sometimes take the form of a white snake, the shrine is especially popular with those seeking success in business.

Access

From Osaka Station, take the Limited Express Super Hakuto (approximately 2.5 hours, about 7000 yen, departures every two hours).

From Kyoto Station, take the Limited Express Super Hakuto (approximately three hours, about 8000 yen, departures every two hours).

Kinosaki Onsen Station and Tottori are connected by the JR Sanin Line. A change of trains is usually required at Hamasaka (approximately two hours, 1340 yen, departures roughly once per hour).

From Himeji Station, take the Limited Express Super Hakuto (approximately 90 minutes, about 4500 yen, departures every two hours).

From Tokyo Station, take a Tokaido/Sanyo Shinkansen to Himeji Station, and change to the Limited Express Super Hakuto (approximately six hours, about 19,000 yen, departures every two hours).

Alternatively, ANA operates several domestic flights per day from Tokyo Haneda Airport to Tottori Airport (75 minutes, regular fare around 28,000 yen).

From Matsue Station, take the Limited Express Super Matsukaze (approximately 90 minutes, about 4000 yen, departures roughly every two hours).