Kamakura Rediscovered - Komachi and Tsurugaoka Hachimangu

A quiet oasis within easy reach of Tokyofs busy streets, the city of Kamakura is perhaps best known for its many historic temples and shrines, set against a tranquil landscape of wooded hills. Spend just a little time here however, and youfll soon find a great deal more to experience, from first rate cafes, bakeries and restaurants to a thriving creative scene.

Arriving into Kamakura Station, a visitor could be forgiven for mistaking this for a typical, if very touristy mid-size town, with rows of simple, even shabby-looking buildings. At a second glance however, one soon starts to spot signs of affluence in its elegant boutiques, cafes and restaurants. In fact, Kamakura has long been one of Japanfs most sought after places to live, and - as a banker friend once confided - one of its wealthiest on average.

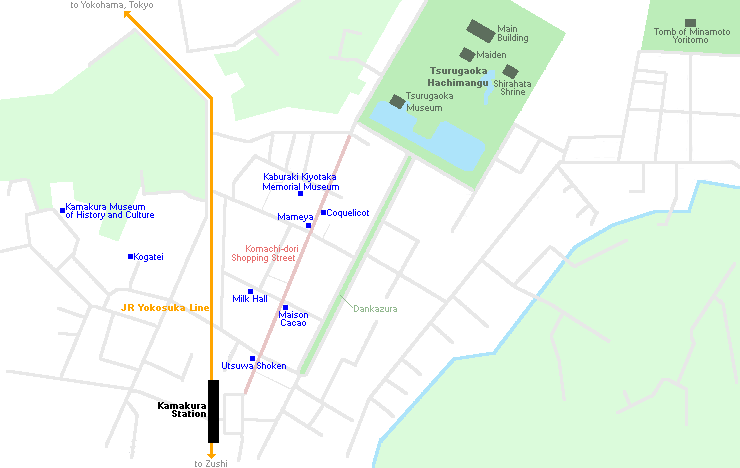

From the station, I take a few steps east before turning onto Wakamiya Oji - a straight, broad street connecting the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine with Yuigahama Beach to the south - whose unique design hints at its historical importance.

Running down the center of the road between its two lanes of traffic is a special raised walkway called the Dankazura, built so that nobles or high-ranking samurai could process in state towards the shrine without stepping into the street itself which for centuries was prone to flooding. Today, the path is open to everyone and lined attractively with stone lanterns and cherry blossom trees.

Approaching the shrine entrance, the road is lined with the usual cafes, souvenir stands and craft stores, many selling finely carved and lacquered wooden dishes in the local style, called Kamakura-bori.

Beginning life as a much smaller shrine complex in Zaimokuza to the southwest, Tsurugaoka Hachimangu was moved to its current location and greatly expanded by the Shogun Minamoto Yoritomo in 1191, following his rise to power in the Gempei Wars. Keen to separate his military government from the endless intrigues of the Imperial Court in Kyoto, Yoritomo chose to make Kamakura his administrative capital with the shrine as its centrepiece.

Arriving at the end of Wakamiya Oji, visitors enter the shrine by crossing one of two flat stone bridges while between them, a third with interconnected pillars and high, elegant arch is fenced off. Known as the Akabashi, this was originally made from red-painted wood and reserved only for the shogun.

The bridges span a short canal between two large ponds, each charged with a special symbolic significance. Bordered with cherry blossom trees and with three islands, one containing a sub-shrine to the goddess Benzaiten, the eastern pond represents the victorious Minamoto (Genji) family, while the western pond, planted with blood-red lotus flowers and four small islands (the character for gfourh being a homonym for gdeathh) represents their defeated rivals, the Taira (Heike).

Making my way further into the shrine complex, I arrive at the maiden, a raised platform of red-painted wood under a gently curving roof, used for public performances and wedding ceremonies. Behind it, I climb 61 stone steps to the shrinefs main building, a quite striking red structure in the Hachiman-zukuri style.

Following a path to the east of the maiden and crossing another small pond, I pass a small gravel enclosure containing a single sakaki tree. Known as a yohaijo, this unique space offers a direct spiritual link to the shrinefs former location - now the Moto Hachiman Shrine - and was used exclusively by the shogun to offer his prayers remotely.

A few steps to the north is the main building of Shirahata Jinja, an attractive smaller shrine recognised as a National Treasure and named for the white banners of the Minamoto family.

Continuing out of the shrine precinct, I thread my way through quiet residential streets to a wooded hill 500 meters to the northwest, where a five-tiered stone monument bearing the Minamoto emblem marks the grave of the shogun Minamoto Yoritomo.

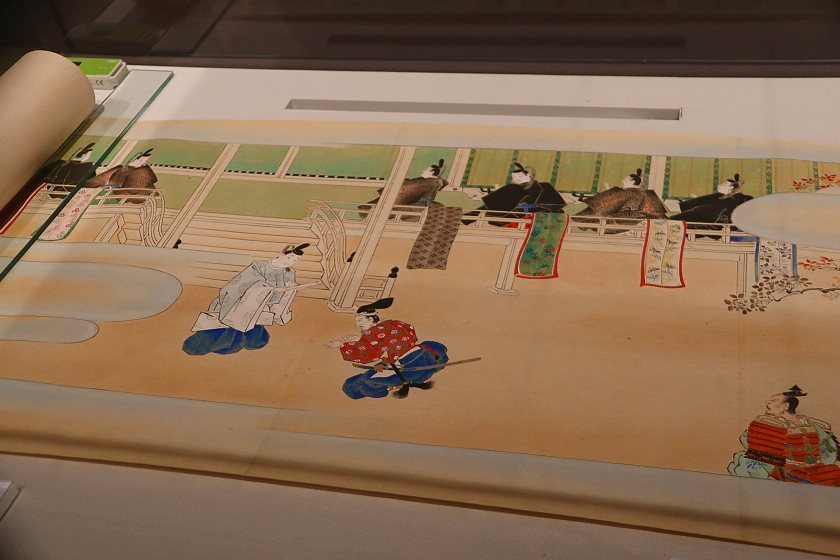

Retracing my steps back through the shrine towards the station, I make a stop at the Tsurugaoka Museum just north of the Heike pond. Designed by a pupil of Le Corbusier, this handsome modernist structure opened in 1951 as Japanfs first public modern art museum. Now owned by the shrine, the museum hosts visiting exhibitions besides a permanent collection of historic local treasures, from finely-carved furniture to sacred objects.

From the shrinefs southwest corner, I make my way back towards the station along Komachi Dori, a popular shopping street with dozens of snack and souvenir stores, and am amazed to find it packed with tourists.

For visitors looking for something sweet, a popular local favorite is Maison Cacao, an artisanal chocolatier chain that famously provided chocolate gateaux to guests at the 2019 Imperial enthronement ceremony.

For something savoury, the endearingly quirky Mameya offers traditional dried bean snacks with flavours ranging from green tea to takoyaki.

In the end, I decide on Coquelicot, an old fashioned hole-in-the-wall selling cheap but delicious crepes, made thin and crispy with a pleasantly nutty taste. Ordering one with lemon and sugar, I settle into a bench and watch as a steady tide of day-trippers flows past.

As well as the usual tourist spots, Komachi Dori also boasts a number of hidden gems for lovers of arts and crafts. Overlooking the street from the second floor of a nondescript building on the western side, Utsuwa Shoken is a particular highlight, showcasing works by local ceramic artists in an attractive gallery space.

By now itfs lunchtime, so I make a stop at Milk Hall, a distinctive building in black-painted wood on one of Komachi Dorifs quiet side streets. Once an antiques shop, the cafe and restaurant maintains a cosy, Taisho-era feel with period knick-knacks and a simple, nostalgic menu.

Nearby, tucked away on another side street at the end of a little garden path, the Kaburaki Kiyotaka Memorial Museum is a small but delightful museum dedicated to a local painter, illustrator and woodblock printmaker. Although modest in size, the collection includes some very accomplished pieces and reveals much about the artistfs creative process.

From there I turned southwest, crossing the tracks leading to the station and threading my way through quiet backstreets dotted with tiny stores, cafes and trendy-looking boutiques.

On my way to my final stop of the day, I pass by a beautiful and very distinctive western-style house set in a wide, leafy garden. Now known as Kogatei, the house was built for a managing director of Mitsubishi in 1916 by the first Japanese architect to be licensed in Britain. After serving as a holiday home to two former prime ministers, it would eventually be bought by the wealthy Koga family and is now an upmarket restaurant and wedding venue.

A short way uphill, I arrive at the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture, an attractive modern building by Foster and Partners, the design team behind the Apple Headquarters in California and the Gherkin Building in London. Inside, the museum covers the cityfs archaeological record from medieval times onward, with a varied and interesting collection divided into five bitesize exhibits.

Exploring the museumfs grounds, I take a short path up to a wooded hillside terrace where a shrine to the god of swordmakers once stood. With my time in Kamakura drawing to a close, I take a few moments to enjoy the sound of birdsong, a trace of incense on the breeze and a view over rooftops to the ocean in the far distance.