Kamakura Rediscovered - Hase

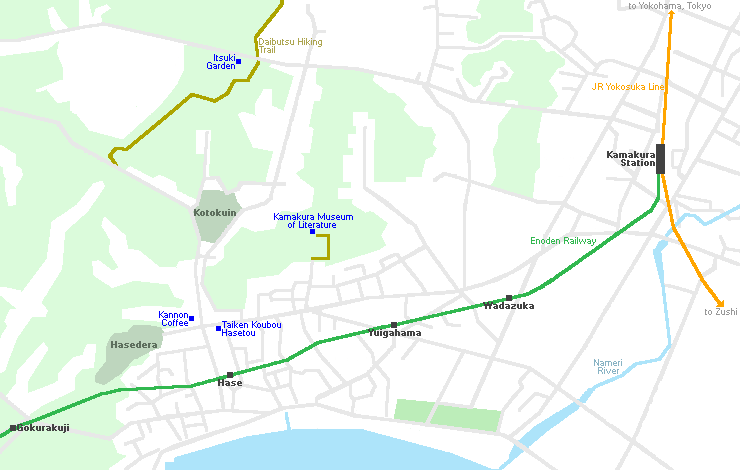

Following on from my last visit to the Jomyoki district of Kamakura, I soon find myself back in town, this time to take a look at the popular Hase district, three stops from Kamakura Station on the Enoden Railway.

By now it's the middle of June - a time of year when the city really comes into its element, with its leafy surroundings looking especially lush and green, and colorful hydrangeas fully in bloom.

Making a slight change from my previous pieces, this time I choose to enter the area on foot via the second half of the popular Daibutsu Hiking Trail, entering just a few steps from Zeniarai Benten Shrine. In the wake of some light early summer showers, the air is thick with humidity and the ground a little muddy underfoot, but still it's a very pleasant trail with a few glimpses of the city below through gaps in the thick undergrowth.

Just as I am making my way over the hill, I come to an attractive open-air cafe called Itsuki Garden, with a series of brick terraces looking out over the treetops below. Originally a private cottage, its owner was inspired to open the space to the public by walkers often getting lost and wandering onto the property by accident. The brick terraces were something of a passion project, added a section at a time over a period of 30 years.

Ordering a light bite to eat, I settle into a peaceful spot and take a few minutes to cool off before continuing downhill into Hase itself.

Arriving back at ground level beside a busy main road, I continue for a couple of hundred meters to my first stop of the day at Kotokuin, a Buddhist temple of the Jodo school best known for one very special inhabitant.

One of Kamakura's best known landmarks, the Daibutsu was completed in 1243, but its story can be traced further back to the reign of Shogun Minamoto Yoritomo - in 1185, he was present at the unveiling of the reconstructed Nara Daibutsu - the original having been destroyed in the Gempei Wars by his now defeated enemies, the Heike. Marvelling at its size and beauty, he resolved to create his own monumental Buddha to adorn his new capital in Kamakura. While he would not live to see it, his vision would finally be realised many years later thanks to tireless fundraising by his former court lady, Inada no Tsubone.

Representing the Buddha of light, Amida Nyorai, the colossal statue was originally housed within a wooden structure, but this was swept away in the 15th century by a tsunami and never rebuilt. The Daibutsu would endure further damage over the centuries from storms, earthquakes and exposure to the elements, requiring various repairs and adjustments. The gilt that once covered the statue has worn away to reveal the bronze underneath, leaving only a slight luminescence around the right temple and cheek.

At an impressive 12.3 meters tall and weighing around 120 tons, the Daibutsu impresses both by sheer size and the powerful sense of sleepy serenity it exudes.

Another interesting building within the temple compound is the Kangetsu or moon viewing hall, a structure that began life in the Imperial Palace of 15th century Seoul.

Just a few minutes from Kotokuin, I make my way along a quiet, shaded driveway to the Kamakura Museum of Literature, located in a distinctive, western-style mansion that was once the residence of Prime Minister Sato Eisaku,

As early as the Edo Period - Kamakura's pleasant scenery, mild climate and close proximity with Tokyo made it the perfect home away from home for high-ranking samurai and other notables. By the 20th century, the area had gained a reputation as something of a cultural hub, with Natsume Soseki and Kawabata Yasunari among its most famous literary residents.

Here at the museum, visitors can find a series of exhibitions highlighting the city's importance to Japanese literature, with letters, manuscripts and other artifacts belonging to some of the country's best known authors of the last century. Even the building itself will carry a special significance to some readers, having featured in Mishima Yukio's classic novel Spring Snow

.

To this day, Kamakura continues to be a magnet for artists, and from hip cafes and boutiques to its many art studios, the city still crackles with a youthful, creative energy. Keen to experience this side of Kamakura life for myself, I made my next stop at Taiken Kobo Haseto, a pottery studio offering beginner experiences from a simple but welcoming space on Yuigahama Dori.

Visitors can choose from a number of different mini-projects - a miniature Daibutsu being an especially popular option - but having always been rather fascinated by the traditional teabowls used in the tea ceremony, I decide to give this a try.

My instructor for the day is Natsukawa-san, an experienced ceramics artist and lifelong Kamakura resident. Taking a seat at an electric potters wheel, he begins by creating an opening for me in a cone-shaped lump of clay, then demonstrating me how to extend and shape it with a light touch of thumb and forefinger.

In a few moments, it's my turn to apply slippery hands to the clay, and despite a slightly wobbly beginning I soon begin to get the hang of it. It's a messy but hugely satisfying experience as the bowl begins to take shape. For me, that's the real charm of ceramic art,

Natsukawa-san agrees, you can get all muddy and return to your childhood.

With a final pinch to add a little bit of asymmetry to the design, my bowl is finished and left to dry. Later, like all guests at the studio, I'll be able to enjoy the final product as Natsukawa-san will apply a glaze, fire it in a kiln and ship it to me afterwards. That really makes the experience twice as great,

he explains, the work arrives, when you've almost forgotten about the feeling of making it, even if things haven't turned out quite the way you were expecting!

With time to spare before my final stop, I enjoy a leisurely stroll around the neighborhood. Not unsurprisingly for a popular tourist area just a short walk from the beach, the Hase area has more than its share of souvenir shops, craft stores and cafes, many with something of a Hawaiian look, reflecting the city's reputation as a nexus for surfers. Along the main street, however, visitors can still find clues to the area's past as a hub for wholesale businesses.

Built in 1918, Anzai Shoten is an agricultural and marine product store whose unchanged appearance, complete with stone foundations, earthen floor and traditional roof tiles, is highly evocative of the Taisho Period.

Turning back along Yuigahama Dori, I make a quick stop at Kannon Coffee, a stylish-looking cafe and coffee stand located just off the main street. I go in fully expecting to order a coffee as usual, but today I'm craving something sweet. When I spot a crepe with frozen berries, cream and a cookie in the shape of the Daibutsu on the menu, there really is only one decision to be made.

After a delicious, sugary snack, I make my way 200 meters to the west to the sanmon or mountain gate of Hasedera, a grand-looking structure of wood and bronze framed by a dramatically curving pine tree. Passing through the main entrance, I enter a spacious precinct with a number of wooden structure and stone steps leading up a steep hillside. All around, in pots, floating in ponds and tucked in amongst the surrounding undergrowth are the colorful hydrangeas for which the temple is best known.

At ground level, one of the temple's most interesting features is a cave known as Bentenkutsu, said to have once been inhabited by Kukai, the revered missionary and founder of Shingon Buddhism. Inside, a low, winding tunnel connects a series of chambers in which statues of the goddess Benzaiten and her offspring have been carved into the rock. Benzaiten is an object of devotion in both Shinto and Buddhism, and symbols of both religions can be found around the cave.

From here, I take a path up the mossy hillside, passing rows of miniature Jizo statues before arriving at the temple's stone paved upper level, containing a belfry, two large halls and an observation deck with a sweeping view of Yuigahama Beach.

Although it began to thrive during the Kamakura Period, Hasedera's origins go back even further to the eighth century, when two skilled carpenters in what is now Nara Prefecture carved two statues of the goddess Kannon from a sacred camphor tree. While one became the centerpiece of a temple in Nara, also called Hasedera, the other was cast into the sea in the hope that its blessings might arrive wherever they were most needed.

The statue would finally wash up on Yuigahama Beach in 736, after 15 years at sea. Standing at over 9 meters in height, it can now be seen in the temple's Kannondo hall - a striking piece of art with a calm but powerfully affecting aura.

Today, the temple is best known for its hydrangea-viewing pathway, leading around the hillside to the southwest and back to the upper level in a gentle loop.

It's perhaps the busiest temple I've visited in the city, but the staff have done an excellent job of controlling the number of visitors entering at one time and there is a wonderful feeling of normality as people of all ages pose for photos, enjoy the flowers and pause to look out over the beach through gaps in the trees.